In what follows, I'm not so much interested in celebrating Dean Mahomet as a "hero" (I don't think he necessarily is one), nor would it mean much to condemn him as some kind of race-traitor. Rather, the goal is simply to think about how we might understand his rather unique book, The Travels of Dean Mahomet, in historical context. What can be learned from it?

* * *

In literary terms, it's probably fair to say that The Travels of Dean Mahomet isn't the greatest book. For one thing, the story Mahomet tells is of his life while he was still in India, and it often seems that the most interesting part of the story is actually Dean Mahomet's life after India and Ireland -- it was only then that he separated from his patrons in Cork, and moved to England and started a series of businesses. Dean Mahomet left a lasting legacy in his trans-culturation of "shampoo" (Hindi: "champna"), and it appears that the word and concept of shampooing (transformed somewhat from his usage, of course) came into widespread usage in the west through him. Fortunately, in Michael H. Fischer's edition of the Travels, there is a substantial account of Mahomet's English experience (click on Part 3).

As a literary text the Travels pales in comparison to, say, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, which was published just five years earlier, and which may have inspired Dean Mahomet to try his own hand at writing an autobiography. Equiano is a spirited autobiography with carefully poised arguments against the transatlantic slave-trade, and indeed, against slavery itself. The author of Equiano cleverly used Biblical references and deployed western/Christian values to force his readers to confront their blindness regarding slavery ("O, ye nominal Christians!").

By contrast, the historical reference points of Dean Mahomet's narrative avoid any negative judgment of British colonial expansion in India whatsoever. In fact, Dean Mahomet clearly marks his perspective as directly aligned with the East India Company's point of view with regard to its military opponents. (His point of view on Indian culture was inevitably different, and his own, or nearly so.) Perhaps it's inevitable that he supported the Company Raj: Dean Mahomet was himself aide-de-camp and then a soldier with the British East India Company's army. He was born in 1759, and left India around 1783 in the company of his "master" (and later, patron), Captain Godfrey Evan Baker, an Anglo-Irish Protestant from a wealthy family in Cork.

Not only was Dean Mahomet associated with the East India Company, but his father was a Sepoy, and died in combat when Dean was about 10 years old. Dean was effectively "adopted" by Baker, and became attached to a European-only regiment. This is really where he mastered the English language, and learned to read and write well enough to be able to think of publishing a book. He certainly did not receive much (or any) formal schooling.

His military association may make us uneasy, but Dean Mahomet's unique status as the only 18th century Indian writer in English was only achieved because of that association. For what it's worth, one notes that Dean Mahomet actually saw very little action during the first decade or so he was associated with Captain Baker. For several of those years, he was a child. And as Michael Fischer points out, even as early as the 1780s, it was the Sepoy regiments that were doing the heaviest fighting in the First Anglo-Maratha War and the Second Anglo-Mysore War. Fischer speculates that Baker and Mahomet, once they were assigned to a more active combat role, may have found their involvement in the subjugation of various opponents of British rule less pleasant. Also, Fischer mentions that Mahomet's patron and friend, Captain Baker, resigned from military service in disgrace in 1782 -- after being convicted of embezzling funds. (Not exactly an uncommon activity for British soldiers at the time; what was less common was to actually be court-martialled for it.)

* * *

Within the book itself, one finds generally two different types of chapters. One type of chapter is more action-based, and tells the story of specific military encounters, experiences, and travels. The other chapters are more essay-like, and in those Mahomet describes in close and appreciative detail aspects of Indian society, religion, and geography for English readers.

On the question of culture, one thing that strikes one immediately in Mahomet's account is that he doesn't seem at all defensive or apologetic about, say, the practice of Purdah, nor does he comment on matters of "race." The former question would be commented on by many later British travelers in India, and would become a key sign of the radical difference of "Oriental" culture in the European imagination -- see how they treat their women! But Dean Mahomet is either unaware of all that, or because he's writing before the exoticism of "Purdah" had been established as a staple of Anglo-Indian writing, he overlooks it:

It may be here observed, that the Hindoo, as well as the Mahometan, shudders at the idea of exposing women to the public eye: they are held so sacred in India, that even the soldier in the rage of slaughter will not only spare, but even protect them. The Haram [Harem] is a sanctuary against the horrors of wasting war, and ruffians covered with teh blood of a husband, shrink back with confusion at the apartment of his wife. (Letter XIII)

In vividly describing how strict gender segregation works, I think Mahomet is supporting the practice. But note the graphic allusion to violence in the last sentence -- doesn't it seem to play into a colonial stereotype? That type of language sometimes makes an appearance in the more military-oriented chapters. For instance, in the passage below Mahomet echoes some of the key tropes of colonial discourse when he uses words like "savages" to describe the hill-dwelling tribes in Bihar:

Our army being very numerous, the market people in the rear were attacked by another party of the [Paharis], who plundered them, and wounded many with their bows and arrows; the picquet guard closely pursued them, killed several, and apprehended thirty or forty, who were brought to the camp. Next morning, as our hotteewallies, grass cutters, and bazar people, went to the mountains about their usual business of procuring provender for the elephants, grass for the horses, and fuel for the camp, a gang of those licentious savages rushed with violence on them, inhumanly butchered seven or eight of our people, and carried off three elephants, and as many camels, with several horses and bullocks. (Letter IX)

Such language is disconcerting -- the word "savage" is an extremely loaded pejorative -- but thankfully, rather rare in The Travels. It's clear that Dean Mahomet values the urban and established northern Indian culture he comes from; it's only the people we would today refer to as "tribals" that get called "savages." (The Marathas, who are often mentioned in the book as military opponents, are never called by that name.)

More common are the chapters in Travels were Mahomet directly describes cultural matters such as Muslim rituals (marriage, circumcision, death), the Indian cities he visits (Calcutta, Delhi, Allahabad, Madras, Dhaka, etc.) and the pomp and pageantry of Indian Nawabs. He liberally uses Persian or Hindi words in these passages, though every so often he finds unusual ways to describe things (Ramadan [he says "Ramzan"], for instance, is described as a "month-long Lent"). A good example might be the following passage on a local Nawab in Calcutta:

Soon after my arrival here, I was dazzled with the glittering appearance of the Nabob and all his train, amounting to about three thousand attendants, proceeding in solemn state from this palace to the temple. They formed in the splendor and richness of their attire one of the most brilliant processions I ever beheld. The Nabob was carried on a beautiful pavillion, or meanah, by sixteen men, alternately called by the natives, Baharas, who wore a red uniform: the refulgent canopy covered with tissue, and lined with embroidered scarlet velvet, trimmed with silver fringe, was supported by four pillars of massy silver, and resembled the form of a beautiful elbow chair, constructed in oval elegance; in which he sat cross-legged, leaning his back against a fine cushion and his elbows on two more covered with scarlet velvet, wrought with flowers of gold. (Letter XI)

As I'm looking over this language, it doesn't seem exactly "neutral" or merely appreciative. It actually seems to ply the language of exoticism to excess. Is that really what Dean Mahomet thought as he watched the Nawab's procession, or is this simply an attempt to create a certain aura of mystery and power for his English readers?

* * *

One of the difficulties in reading Dean Mahomet's rhetoric about India during the early Company Raj is the fact that he apparently plagiarized a number of descriptive passages from British travel writers, especially John Henry Grose's Voyage to the East Indies (1766). That's right -- here we have a very early Indian writer born and raised on the Gangetic plains, plagiarizing descriptions of key Indian cultural matters from a British writer! According to Michael Fischer (see his comments in Part 3), about 7% of the text of The Travels actually comes from other sources. Why Mahomet chose to do this is open to speculation -- perhaps he simply hadn't encountered certain things, and used Grose to fill in certain gaps (for instance, he knew a lot about Muslim religious practices from personal experiences, but actually knew surprisingly little about Hinduism; he gets some key things wrong in his account of caste in the book). Or it's possible that he simply liked the way Grose and others put things, and borrowed the language out of sheer laziness. Who knows? (One might also note that modern ideas about copyright and copyright law were still in a formative phase in the late 18th century.)

The plagiarism issue brings us back to Equiano, albeit somewhat obliquely. In a 1999 article in the journal Slavery and Abolition, Vincent Carretta argued (I think, convincingly) that Gustavus Vassa was in fact not born in Africa at all, as he states in The Interesting Narrative, but rather South Carolina (see this article in the Chronicle of Higher Ed, and this follow-up colloquy). According to Carretta, some of the text from the first three chapters of Equiano's book, describing Equiano's life as a child in Nigeria, and subsequent capture by slave traders, are in fact taken from a Quaker traveler named Anthony Benezet. Equiano probably invented a different early life to strengthen his point about the evils of slavery and the slave-trade: the disruption of the idyllic African childhood makes a better story than being directly born into slavery, which is what probably happened. Carretta also shows that nearly everything Equiano describes as happening to himself in his adult life can be verified by historical documents.

One thing I get from both of these "plagiarism" cases is a distinct sense that, while both books are remarkable and surprising in their own ways, neither author was fully in command of an individualized "voice" as he wrote. Both Gustavus Vassa/Equiano and Dean Mahomet were always in some sense writing within the existing conventions of English travel literature of their day. The fact that they even borrowed aspects of their own self-description from English writers only reinforces how precarious their respective authorial positions were.

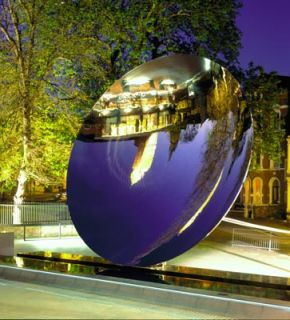

Minimalism came of age in the 1960s, and was displaced somewhat by postmodernism and conceptual art, though it never really went away. For the most part I tend to prefer more congenial, conversational art, but a number of Kapoor's pieces do something for me that Donald Judd's roomfuls of black cubes don't really do. Kapoor's best works clearly are social objects, even if they operate in the same general mode as minimalism does.

Minimalism came of age in the 1960s, and was displaced somewhat by postmodernism and conceptual art, though it never really went away. For the most part I tend to prefer more congenial, conversational art, but a number of Kapoor's pieces do something for me that Donald Judd's roomfuls of black cubes don't really do. Kapoor's best works clearly are social objects, even if they operate in the same general mode as minimalism does. What I like about the "Sky Mirror" piece and a related piece now installed at Millenium Park in Chicago called "Cloud Gate" is the way they present a kind of prism through which to view the world. They are solid, stainless steel, and point at the monumental architecture around themselves -- and in that sense they are completely of a piece with the modern American city. But in that they have the general look of liquids, they resist the sense of fixity of massive public sculptures, which are sometimes more in the vein of decorative buildings than art objects that inspire contemplation. As the Times notes, in the convex mirror of "Sky Mirror," the towering buildings facing the sculpture are vertically inverted -- another kind of anomaly.

What I like about the "Sky Mirror" piece and a related piece now installed at Millenium Park in Chicago called "Cloud Gate" is the way they present a kind of prism through which to view the world. They are solid, stainless steel, and point at the monumental architecture around themselves -- and in that sense they are completely of a piece with the modern American city. But in that they have the general look of liquids, they resist the sense of fixity of massive public sculptures, which are sometimes more in the vein of decorative buildings than art objects that inspire contemplation. As the Times notes, in the convex mirror of "Sky Mirror," the towering buildings facing the sculpture are vertically inverted -- another kind of anomaly.