I was recently asked to give a short statement at an interfaith event in Doylestown, sponsored by Rise Up Doylestown, Showing Up for Racial Justice, and a number of other groups. This is the text of what I presented at that event.

Statement for “Many Faiths, One Community” Event (June 11, 2017)

When 9/11 happened, I had just moved to this area from North Carolina for my first real teaching job at a university. I was living alone in downtown Bethlehem, near a high school. I was numb from the horror of the attack and from spending a little too long watching the coverage of it on the news.

But I was also afraid for myself. I didn’t go out much that fall and when I did I felt myself under scrutiny. I heard a lot of hostile, even hateful comments. Driving, I was threatened by other motorists. The comments were of a certain stripe: “Osama,” “Taliban,” “Saddam.” Sometimes the harassers tried to sound mean and friendly at the same time: “What’s up, Bin Laden?” When I flew to a conference in Wisconsin that November, the woman sitting next to me on the plane was immediately uncomfortable. She asked to change seats, and the flight attendant agreed. I was horrified, but I understood that this was going to be part of life in America. The country where I had grown up, which I thought of as my country -- my home -- had become something strange and newly hostile. I had to learn to accept those sorts of reactions. And on the whole I was lucky. I faced no physical violence; others in my circle of friends and family did. I didn’t have to worry about my job security or my visa status; others I knew did. And after a couple of years people seemed to calm down and I could begin feel a bit more comfortable in public places. I could start to go on with my American life.

When the 45th President was elected this past November, I couldn’t help but remark to friends and family that it felt a little like 9/11 all over again. I couldn’t understand how so many people thought this man would be good for the country. His comments about planning to ban Muslim immigration in particular seemed unthinkable to me: unconstitutional and just plain wrong. But then he won, partly on the basis of his very racism, xenophobia, and hatred of Muslims. And again, the country that I thought I knew turned out to be something stranger and darker than I had thought.

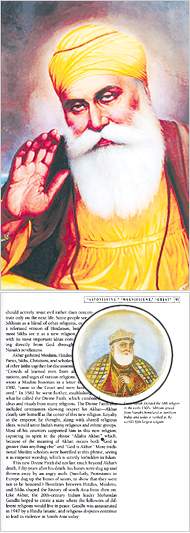

It is probably important to mention at this point that I am not a Muslim but a Sikh. Beause of my turban and beard we are often confused here in the U.S. Sikhism is a faith based on egalitarianism, a strong sense of social obligation to others, and courage when faced with hostility. In our tradition, we tell the story of the tenth Sikh Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, who when the Sikh community was under threat from the Mughal Emperor who ruled India in 1699 established the idea of a distinctive Sikh identity -- the Khalsa. From this point forward every Sikh would be identifiable, even if it made them a target. A fateful decision, but a powerful one.

I don’t regret the hostility that is directed towards me by mistake. I embrace it. Today, when I have been the target of anti-Islamic hate-speech I have always tried to make it a point not to simply say, “I’m not a Muslim” -- because that person is definitely going on to target someone else. The better strategy is to stand with my Muslim brothers and sisters against all such hatred. Because if we are going to stay here in this country -- if we are going to find a way to make it feel like home again -- we have to stand together against intolerance directed against all religious and racial groups. That’s why I also think it’s important to support my Jewish friends who are facing a resurgence of anti-Semitism at present as well. Why we need to support and stand with our LGBTQ friends and allies. And why I think it’s important to say “Black Lives Matter.”

In one sense the election of President #45 hasn’t led to the kind of overnight and blanket hostility people who look like me once faced every time we went outside. But what it has unleashed has been a new mainstreaming of extremely intolerant and hateful speech, not just on the streets, but in the mainstream media and in government. That’s what the so-called “March Against Sharia” that is taking place in cities around the country today is. In response I think it is important not just to stay home and stay inside, but to go out on the streets to do counter-marches, to gather at events like this one. To find allies and support each other as we face the long and dangerous road ahead. Thank you

Statement for “Many Faiths, One Community” Event (June 11, 2017)

When 9/11 happened, I had just moved to this area from North Carolina for my first real teaching job at a university. I was living alone in downtown Bethlehem, near a high school. I was numb from the horror of the attack and from spending a little too long watching the coverage of it on the news.

But I was also afraid for myself. I didn’t go out much that fall and when I did I felt myself under scrutiny. I heard a lot of hostile, even hateful comments. Driving, I was threatened by other motorists. The comments were of a certain stripe: “Osama,” “Taliban,” “Saddam.” Sometimes the harassers tried to sound mean and friendly at the same time: “What’s up, Bin Laden?” When I flew to a conference in Wisconsin that November, the woman sitting next to me on the plane was immediately uncomfortable. She asked to change seats, and the flight attendant agreed. I was horrified, but I understood that this was going to be part of life in America. The country where I had grown up, which I thought of as my country -- my home -- had become something strange and newly hostile. I had to learn to accept those sorts of reactions. And on the whole I was lucky. I faced no physical violence; others in my circle of friends and family did. I didn’t have to worry about my job security or my visa status; others I knew did. And after a couple of years people seemed to calm down and I could begin feel a bit more comfortable in public places. I could start to go on with my American life.

When the 45th President was elected this past November, I couldn’t help but remark to friends and family that it felt a little like 9/11 all over again. I couldn’t understand how so many people thought this man would be good for the country. His comments about planning to ban Muslim immigration in particular seemed unthinkable to me: unconstitutional and just plain wrong. But then he won, partly on the basis of his very racism, xenophobia, and hatred of Muslims. And again, the country that I thought I knew turned out to be something stranger and darker than I had thought.

It is probably important to mention at this point that I am not a Muslim but a Sikh. Beause of my turban and beard we are often confused here in the U.S. Sikhism is a faith based on egalitarianism, a strong sense of social obligation to others, and courage when faced with hostility. In our tradition, we tell the story of the tenth Sikh Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, who when the Sikh community was under threat from the Mughal Emperor who ruled India in 1699 established the idea of a distinctive Sikh identity -- the Khalsa. From this point forward every Sikh would be identifiable, even if it made them a target. A fateful decision, but a powerful one.

I don’t regret the hostility that is directed towards me by mistake. I embrace it. Today, when I have been the target of anti-Islamic hate-speech I have always tried to make it a point not to simply say, “I’m not a Muslim” -- because that person is definitely going on to target someone else. The better strategy is to stand with my Muslim brothers and sisters against all such hatred. Because if we are going to stay here in this country -- if we are going to find a way to make it feel like home again -- we have to stand together against intolerance directed against all religious and racial groups. That’s why I also think it’s important to support my Jewish friends who are facing a resurgence of anti-Semitism at present as well. Why we need to support and stand with our LGBTQ friends and allies. And why I think it’s important to say “Black Lives Matter.”

In one sense the election of President #45 hasn’t led to the kind of overnight and blanket hostility people who look like me once faced every time we went outside. But what it has unleashed has been a new mainstreaming of extremely intolerant and hateful speech, not just on the streets, but in the mainstream media and in government. That’s what the so-called “March Against Sharia” that is taking place in cities around the country today is. In response I think it is important not just to stay home and stay inside, but to go out on the streets to do counter-marches, to gather at events like this one. To find allies and support each other as we face the long and dangerous road ahead. Thank you