The New York Times is essentially perfect in its review of a current major exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, on the painter Nandalal Bose. The exhibit was put together by the San Diego Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi (which is also, incidentally, very much worth a visit). We went there a couple of weeks ago, and enjoyed it (though it certainly helps that the Philadelphia Museum of Art has a play area for children in the basement; otherwise, 2 year olds and art museums are usually not compatible.)

The key question the exhibit addresses is: what did it really mean to make "modern" art in an Indian idiom in the latter years of the British Raj? From the dominant colonial point of view, there was no such thing as "modern Indian art": by and large, the British were mainly interested in ancient Indian art, including traditional Indian art produced in the modern era. (One prominent exception was Ernest Binfield Havell, who actively supported Bengali artists who aimed to invent a modern style in Indian painting.)

Probably the best known Indian artist in the era just before modernism took hold was Raja Ravi Varma, who painted in the academic realist mode of 19th century western art. He made some very accomplished paintings, like this one, for example, but critics found his direct emulation of European painting styles unsatisfactory.

The modernist school that emerged at Santiniketan, with Rabindranath Tagore as a kind of god-father, and Rabindranath's nephew, Abanindranath Tagore as the most talented early painter, aimed to move away from academic realism, and towards a style of painting that was at once distinctly modern and formally and thematically Indian.

Sometimes, the path wasn't entirely clear -- several of the major figures in the Bengali school, after rejecting European realism, embraced Japanese minimalism instead. Indeed, a number of Nandalal Bose's own paintings do this. Perhaps they found the Japanese style less foreign; it wasn't until the 1930s that it became apparent that Japan could be every bit as "Imperialist" as western nations. In any case, for the most part Indian artists moved away from the influence of Japanese art as well in the 1920s and 30s. (The artist who did this most brilliantly might be Nandalal Bose's student, Benodebehari Mukherjee, who probably deserves his own show.)

The weak part of the current exhibit from an aesthetic point of view is probably the series of paintings and linocuts from Bose's "nationalist" period, in the 1930s and 40s. Some of Bose's work from that era became quite famous, including this linocut of Mahatma Gandhi, from 1940. But the paintings Bose did for the meetings of the Indian National Congress (the Haripura Congress of 1938) seem overly simplistic -- works of propaganda, not personal inspiration.

I did find some of Bose's paintings of tribal life in Bengal (of the Santhal community) quite powerful: see New Clouds, for instance. These are paintings Bose was doing around the same time as he was painting large religious murals on commission, and nationalist posters for the Congress Party. But they are quite different from those other works. Bose's paintings of tribals aim to quietly capture a local reality, not a magnified, iconic myth of Indian nationhood.

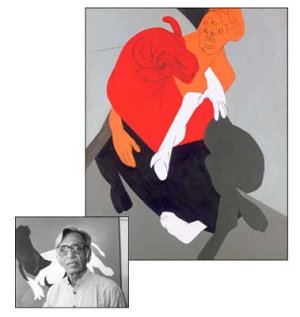

The last room of the exhibit has paintings by recent Indian artists who have been clearly influenced by Nandalal Bose and the Santiniketan school. I was particularly impressed by Atul Dodiya and K.G. Subramanyam, both of whom are painters I'd like to see more of.

If you're going to be in Philadelphia in the next couple of weeks, I would definitely recommend you check out this exhibit. Otherwise, you might catch it in India (where the show is headed next).